In the course of gearing up for my big lecture on Yoga Sutra I had come across a dramatic story that even Wikipedia mentions in its entry. I’ve called it “The Legend of Lost Sutra”. If briefly, the legend tells that Yoga Sutra, a sacred text known in India from ancient times, practically sank into oblivion in the 12th century and was recovered only in the 19th, owing to Vivekananda and the Theosophical Society.

The text fell into obscurity for nearly 700 years from the 12th to 19th century, and made a comeback in late 19th century due to the efforts of Swami Vivekananda, the Theosophical Society and others. It gained prominence again as a comeback classic in the 20th century.

However, this is not how the real story goes.

The first reference to Yoga Sutra – actually, not the Sutra itself but one of its commentaries, the Rājamārtanḍa of Bhoja – can be found in the book The Hindoos: Writings, Religion, and Manners of W. Ward, an English Orientalist.

While a work that appeared 20 years after – the book of another prominent Eastern scholar, H. T. Colebrooke, that was published in 1835 – can be already seen to contain a lot of information about Yoga.

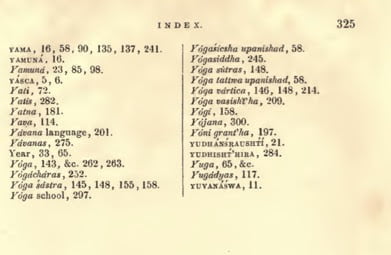

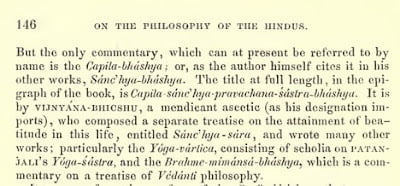

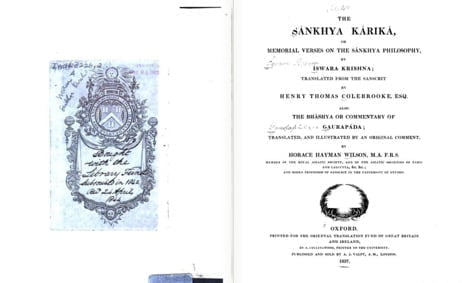

As one can see from the index photo, the book mentions Yoga Sastra, schools of yoga, yoga siddhis, Yogatattva Upanishad and Yoga Sutra proper together with its key commentaries: Yoga Bhāṣya, the already mentioned Rajamartanda and Yoga Vartika, as well as Yoga Vasistha and many other treatises. In fact, it provides a complete list of Yoga most significant texts. And these are not mere references – we see that the author was familiar with the texts contents as a minimum. By the way, the book comes almost concurrently with Colebrooke’s first translation of Sānkhya Kārikā with commentary of Gaudapada.

This is a very important yoga text and a prominent philosophical piece. Yet what stroke me most was the fact that European scholars had translated it such a long time ago. By the way, Colebrooke also authors a very interesting book on Sanskrit in that he gives intelligible exposition of its grammatical issues – the book that I had a pleasure to thumb through.

Now, if we take a look at a page from the book published in 1835 and mentioning almost all commentaries on Yoga Sutra, what deduction can we draw? With Sir William Jones’ report taken as a reference point, the interaction between Oriental studies, English scientific culture and Indian culture by that time had gone back some 50 years only. Still, by the time considered they had already managed to collect an exhaustive list of different Yoga Sutra commentaries.

So what does it all add up to? To my mind, hence comes a very simple conclusion. In the scope of Indian tradition they never forgot Yoga Sutra. The class of Brahmans involved in first contacts with Europeans knew it perfectly well. It was neither classified, nor lost, nor forgotten; thus everything about it came on surface in the earliest years of cultural interaction.

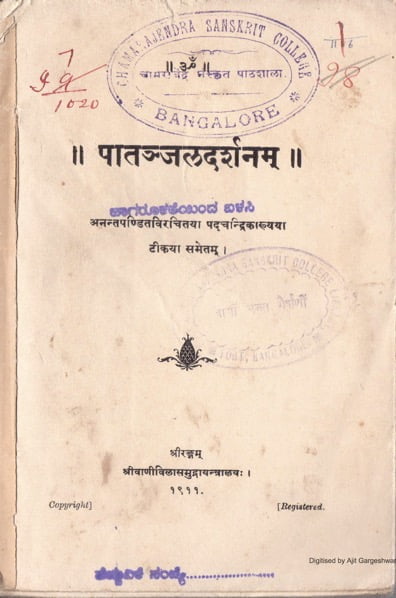

This opinion is evidenced by the abundance of commentators’ literature written by Indian pandits during the period of “oblivion”. In addition to famous Vijnana Bhikshu, the author of the well-known Yoga Vartika (XVI cent.), we know a lot of other commentaries, including the late ones. For instance, Sadasivendra Sarasvati’s Yoga Sudhakara (XVIII cent.) and the text of Anantapandit that came even later.

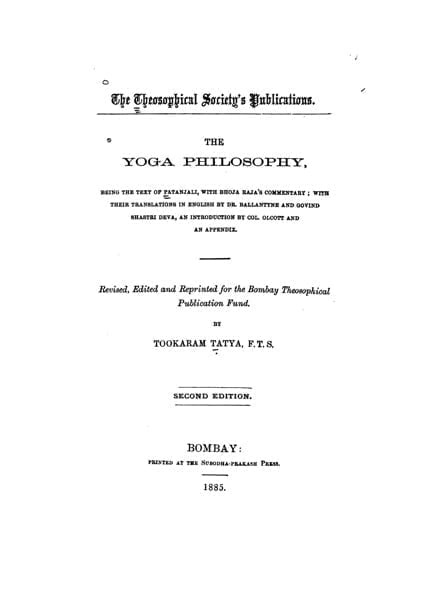

As to the Theosophical Society, its role in this story has been a bit of a stretch. Indeed, the second, the best known edition of Yoga Sutra first translation made by Dr. Ballantyne was issued under the aegis of the Theosophical Society. It comes with its headings, while the introduction was written by Coll. Olcott.

However, this was just a reedition that appeared 30 years after the text original translation.