This unscheduled article has been induced by my short post on Facebook. A couple of days ago my sight was caught by an ad of “Patanjali Hatha Yoga” event in Kharkov, and I could not but turn the yoga community attention to incorrectness of this word combination. They started speaking about Hatha Yoga in the period of the Naths, that is, 600 to 800 years after Yoga Sutras had been written. As to Sutras, they don’t give any specific descriptions of asanas or pranayamas. In a short discussion commenting the post Boris Zagumennov, a man I hold in high regard and one of the first interpreters of Sutras from Sanskrit into Russian, advanced an idea that though Patanjali does not, of course, use the term “hatha yoga” he, however, speaks about “stages that refer to body”. This is a very popular point of view; moreover, I also personally stick to the idea that proper body work is essential prior to taking to more complex and sophisticated yoga practices. But! My personal (or, say, the common and traditional) opinion is one thing, while the opinion of Patanjali and commentators is a totally different issue. Indeed, Patanjali did mention asana and pranayama as constituents of yoga, but were these terms of his identical to their present-day meaning?

For a man of today working with one’s body first of all implies its training aimed at changing and improving its corporal, primarily aesthetic conditions. This is the approach we’ve inherited from the Ancient Greeks to whom the credit thus goes. And this is the vein yoga practiced in most [fitness] clubs. The “yoga” of this kind may be good or bad for one’s body, depending upon the teacher’s qualification, but we must honestly admit it to be European gymnastics, and singing OM or “visualizing” different things won’t help. So politically correct oriental scholars of Europe have coined a respective “inoffensive” term by calling this practice “postural yoga”.

A different approach to the practice was developed (and called “hatha yoga’) in India by ca. the end of the first millennium. This system was antithetical to Greek body aesthetics and its exertion technique but was impregnated with ideas of Indian pharmacy (Rasayana) and Tantra, and advanced two fundamental ideas concerning the body.

The first concept is psychosomatics, that is, a method of affecting one’s state of mind with the help of the body. The Naths were the ones who elaborated the subject to the best. They happened to notice not only the association between emotional states and different body parts, but also the even more profound correlation between mind and breathing – and thus laid the theoretical groundwork of pranayama practices. Let me draw a few examples:

dugdhaṁbuvat sammilitau sadaiva tulyakriyau mānasamārutau ca

|

yāvan manas tatra marutpravṛttir yāvan maruc cāpi manaḥpravṛttiḥ || (27)

Just like water and milk when mixing up become one, the same mind (manas) does with breathing. Wherever the mind, there goes breathing, wherever breathing, there goes the mind.

(Amanaska).

The meaning of this line is clear for those who’ve worked with body and emotions. One breathes with a zone in which their actual emotions are located. And vice versa: activation of a chakra emotional experience boosts corresponding body zone involvement in the process of respiration. Hence comes the idea that a “thin” (chitta, mind, manas) can be controlled with the help of a “rough” – breathing. That is the idea of pranayama.

This line develops the idea of Patanjali who wrote in this respect that pranayama gives stability of chitta and manas’ ability to concentrate. But the pathos (and, probably, the degree of the subject development) of the medieval texts is much stronger. Yoga Bija, for instance, states that:

cittam prāṇna sannaddhaṃ sarvajīveṣu saṃsthitam।

rajjau yadvatparībaddhā rajvī tadvadime mate॥(79)

Just like one rope is bound with another one, mind [citta] and prana are bound in all living beings.

nānā vidhairvicāraistu na sādhyaṃ jāṇate manaḥ

tasmāttasya jayopāyaḥ prāṇa eva hi nānyathā॥(80)

Different practices of vicara shall not help attain control over the mind. Thus the only (!) means of keeping it under control is prana.

In developing this concept Gorakshashataka advances an even bolder, almost extreme idea of pranayama to be an instrument of both spiritual deliverance and overcoming karma:

prāṇāyāmo bhavatyevaṁ pātakendhanapāvakaḥ |

bhavodadhimahāsetuḥ procyate yogibhiḥ sadā || 10 ||

Pranayama is fire which firewood is made of faults (pataka). Yogis always call it a grand passage across the ocean of being.

Even though this opinion seems to be totally surprising, it has its inner logic. Indeed, if karma has psychologic nature and comes as manifestation of sanskaras and vasanas (this is what Patanjali wrote about), it is then subject to changes through working with one’s mind. Early sources on yoga, including Patanjali (and even Bhagavad Gita) proposed knowledge (jnana) to be an instrument of such changing. So there is a principal difference here.

Today the practicians who seriously treat body as a key to working with one’s psyche and are sufficiently competent in this issue are few in number, though it is exactly what makes the essence of hatha yoga.

The second idea of the medieval yoga lies in possibility of physical body qualitative transformation. In this case, it is related to feasibility of control over physiological functions that might in future result in longevity that are considered, rather than aesthetic conditions. Yoga Bija, a medieval treatise, writes the following:

śarīreṇa jitā sarve śarīraṃ yogibhirjitam।

tatkathaṃ kurute teṣāṃ sukhaduḥkhādika phalam॥(49)

Everyone is conditioned (conquered) by the body, while the body is conquered by yogis. How can they be affected by fruits of pleasure or suffering?

Another quotation from the same source illustrates the principle of body transformation:

apakvāḥ paripakvāśca dvivadhā dehinaḥ smṛtāḥ

apakvā yogahīnāstu pakvā yogena dehinaḥ

34. Those having body are of two kinds: “immature” (apakva) and “mature” (paripakva). Immature are those who lack yoga, while maturity is attained by means of yoga.

But were these approaches – the training method of the Greeks or the alchemic system used by the Naths – valid for Patanjali?

Let us figure it out drawing on the example of asanas.

The term āsanam stems from the root ās – to sit – by means of adding the suffix -ana that creates the name of an action. Thus, asana means “sitting”. In this sense the phrase “standing asana” is an oxymoron that emerged after numerous modifications of the term original meaning.

Yoga Sutras give a clear definition of asana:

Sthira-sukham āsanam ॥ 46॥

Asana is what [tends to be] steady and pleasant.

As we see, this definition lacks any reference to body “training” or “keeping under control”. One can hardly condition or stretch something by staying in a pleasant and comfortable pose.

The author of YS does not offer a more detailed explanation, let alone a list of asanas. The list, however, can be found in the work of Vyasa, while a very short description of asanas’ performance is given by Vyasa’s commentator, Vachaspati Mishra. So let us take to studying these lists.

Vyasa is very concise, and his comment to the line 2.46 comes as a mere recapitulation of asanas:

॥2.46॥ tadyathā padmāsanaṃ vīrāsanaṃ bhadrāsanaṃ svastikaṃ daṇḍāsanaṃ sopāśrayaṃ paryaṅkaṃ krauñcaniṣadanaṃ hastiniṣadanam uṣṭraniṣadanaṃ samasaṃsthānaṃ sthirasukhaṃ yathāsukhaṃ cetyevamādīni।

Some of them are familiar to us: Padmasana, Virasana (though there is a nuance here that I’ll come back to later), Svastikasana, Bhadrasana, Dandasana. Others have not been made part of modern guidelines on yoga: the seated heron pose (krauñcaniṣadanaṃ), the seated elephant pose (hastiniṣadanam), as well as the pose of camel who does the same (uṣṭraniṣadanaṃ). It is also not clear what they mean by the “supported” pose (sopāśrayaṃ) and paryaṅkaṃ – the asana which name can be translated as “lying” as well as “squatting” pose. To explain all above let us turn to the sub-comment.

As to the lotus pose, Vachaspati Mishra does not even explain it and simply writes that:

padmāsanaṃ prasiddham।

The lotus posture is well-known

Most probably, this pose was popular 1000 years ago.

As to the ‘supported pose”, Mishra gives the following elucidation:

yogapaṭṭakayogāt sopāśrayam।

i.e. [this pose is called so] because the body (kaya) is bonded (yoga) by yogapatta – a special-purposed rope.

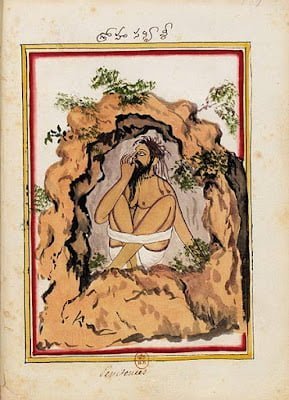

Perhaps it looked in the following way:

Vachaspati’s explanation of seated heron, elephant and camel poses is rather ironic:

krauñcaniṣadanādīni krauñcādīnāṃ niṣaṇṇānāṃ saṃsthānadarśanāt pratyetavyāni।

The heron and other seats may be understood by actually seeing the seated animals.

So let us try to observe them the way we can. For instance, by web-browsing:

What is evident about these poses is THEM BEING SIMPLE. The elephant does not look like it’s doing the workout, while the camel does not seem to be overcoming the body. All these are simple seating or lying poses that one can easily do, they don’t imply exertion and don’t exercise the body. Sure, for a European individual who’s been “tensed” by cold climate and corresponding nutrition mode assuming the lotus pose or Bhadrasana may seem to be a daring deed or even the goal of yoga, but for a man of Hindu anthropologic type these are truly comfortable and stable poses. A shopkeeper selling betel pepper in a small cabin can easily spend all day long sitting in Svastikasana or Bhadrasana.

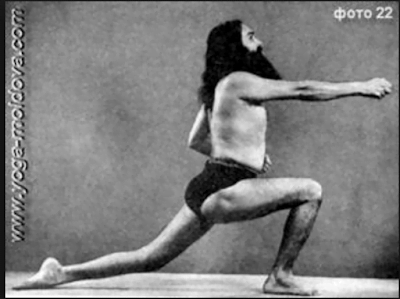

An attentive reader might ask here: and what about Virasana? We know it to be like this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

However, there’s got to be a catch here. The pose known as Virasana in the course of time has been subject to numerous modifications – fundamental modifications. This can be found in J. Mallinson’s reports. Even today different schools teach a different performance of the pose they call Virasana. Sometimes it is identified with Virabhadrasana, Hanumanasana and others, and sometimes it is not. For instance, the Virasana of Iyengar School looks differently:

But what was the Virasana of Vyasa? We have the description given by Vachaspati Mishra:

sthitasyaikataraḥ pādo bhūmyasta ekataraś cākuñcitajānor upari nyasta ity etad vīrāsanam।

A sthita [man] has one leg on the ground and the other leg is placed over it with a bent knee – this is Virasana.

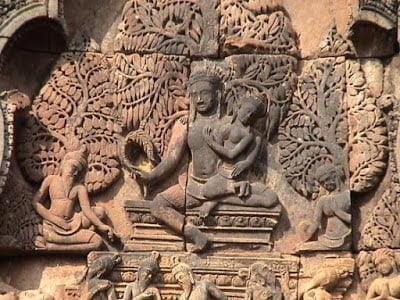

The description is terse and it is difficult to say how it really looked like. Moreover, that the word sthita may refer both to a person sitting on a bench and a standing one. But it definitely did not look like the above-shown standing pose. I think they mean here a pose that resembles Classic Indian sitting on a throne. Like Shiva’s pose on the image below:

So what am I driving at?

All poses described in early commentaries were not of training kind. Neither have they the effect of body “subordination”. These are just poses that are comfortable for meditation or doing pranayamas. At the times of Patanjali mastering an asana had nothing to do with body tough workout. It was the ability to assume meditative poses for a long period of time without making the – what we would call today – neurotic moves. The yoga of Patanjali is a system of psycho-techniques. As to the stemming of other concepts, in particular, those body-oriented – the developing and therapeutic approaches – they result from the next stages of evolvement of Yoga as a Tradition.