A long time ago when I was just starting my study of yoga – guess it was 1986 or 1987 – one of my groupmates came with a clandestine reprint of a brochure made with the help of factory printing office. Though, it was not even a brochure: just several unbound sheets bearing the title Patanjali’s Aphorisms. And it is this text – that I later learned to be the reprint of Yoga Sutras English version in the translation of Vivekananda as rendered [into Russian – trans. note] by Popov in 1906 – that my journey into the insights of this great text started with.

In a few years (these were probably early 90ies) I suggested that my friends who had organized a kind of esoteric publishing house bring together all YS translations available at that time and arrange them sutra by sutra to help one’s working with this text. Studying Sanskrit was just a plan for the future and I thought that understanding the true contents of the text would be possible on the basis of the translations comparative analysis. The translations that were vastly different even on the surface. This is how the brochure Yoga Sutras: Four Variants of Translation appeared. Soon it was complemented by the fifth one, while the brochure formed the basis of the file Yoga Sutras: Five Variants of Translation that’s been actively circulating throughout the web [the Russian-speaking segment – transl. note]. Though, maybe I was not the only one whom this idea actually occurred…

Anyhow, I believe this file has helped may searchers and practitioners, but I think it’s time every translation version is given a detailed and competent estimation.

The translation of Swami Vivekananda

First of all I should say this translation is rather good as an independent text. There is a particular individuality in it; it is rather simple and inspiring, and it encourages to ask further questions. In addition to this we should admit that due to simplicity of its English the translation of the text into the Russian language has been rather precise.

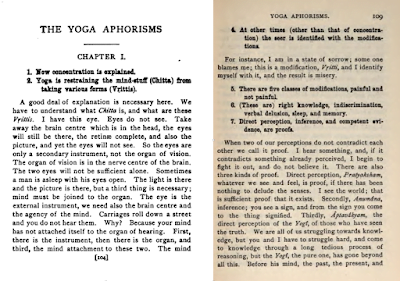

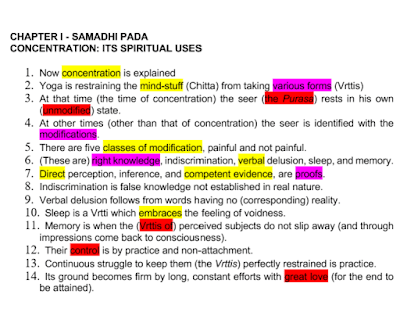

Some 15-20 years ago Vladimir Danchenko made another attempt of rendering the text from English into Russian (this version is available in the Internet), though in actual fact other than having eliminated a few irregularities he has not changed the text much. Nevertheless, even in consideration of the fact that I think the translation of Vivekananda to be reasonably good, it still has a vast number of faults. Besides it is obvious that the translation was substantially affected by Ballantyne’s translation of Yoga Sutras with the commentaries of Bhoja. And I would actually wonder whether the translation of Vivekananda is a totally independent work. Let us study the first page of his version [the author originally analyzes the Russian translation of Vivekananda’s rendering of YS, but as the Russian target text in this respect follows the English source text, we’ve done the same with the English one – transl. note].

I have marked in red the words that were absent in the original text. We can see Vivekananda to have added many “extra” words to the original lines. Most of these words had been borrowed (as if had stuck to the basic text) from the commentaries of Bhoja-vritti, and in this context one cannot claim they are absolutely odd. But if truth be told, we understand that we somewhat modify our understanding of Yoga Sutras by adding the tint of Bhoja’s ideas. Besides let us note that Vivekananda sets forth the text of the sutra only, and in order to explain these extra words we should admit he was familiar with Bhoja-vritti, either the original text or the translation of Ballantyne.

The yellow colour highlights the words that have been translated either not very precisely or in the way they restrain or trivialize the sense. For instance, “Now concentration is explained.” But the text reads as atha yogānuśāsanam – “now yoga is explained.” One may of course translate the word “yoga” as “concentration”, but in the next line yogaścittavṛttinirodhaḥ the word “yoga” is preserved. There is a piece of carelessness here, isn’t there? Especially if we take into account the fact that he uses the word “concentration” to further translate “samadhi” This results in confusion of the text terminology.

And finally the purple is used to show the cases in that one and the same Sanskrit word is interpreted with the help of different terms, that, as you understand, perplexes the reader even more. For instance, the “pramana” vritti in one case is translated as “right knowledge” (1.6.) (that, to be absolutely honest, is not an exact variant), while in the other line it is translated as “proofs”(1.7.) The same with the word “vrittis”: it is translated as either “forms” (1.2.) or “modifications” (1.4.). The latter complies with vritti as understood by Bhoja who explained vritti as “parinamas” – modifications.

If watching this one page does not do, I shall give a detailed explanation of some highlighted issues to a more meticulous reader. Others may skip the part and proceed reading the analysis of the second text.

Vivekananda translates “chitta” as the “mind-stuff” (1.2.). This has been definitely borrowed from Ballantyne’s work.

To speak frankly, the idea of substantiating chitta is not that evident, though really insightful. Later translators gave up the concept – though they had better not.

In the 3rd sutra “drashtar” – “the seer” – is identified with purusha that “rests in his own (unmodified) state.” This translation very much taints and simplifies the understanding [of the practice]. The term “drashtar” indeed stems from the root-word “ddṛś” – to see, drashtar is the one who sees, and “tada drashtuh svaroope avasthanam” means “then the drashtar rests in its own state, its innate form.” Drashtar is the feeling of the inner observer. It is a specific mind experience. While when we say “purusa” we turn to another type of experience. The word “purusa” derives from the root “pur”. It has been preserved in Russian in the word “polnyi” [meaning “full”. The English “fill/full” in the same meaning also stems from this PIE root *pele- (1 )– transl.note]. The experience of “purusa” is self-awareness of one’s inner substantival “Self”, and this is a totally different – this time a substantial one – view of the subject inner essence. From phenomenological description of the first shloka we shift to an objective-substantive mode. And here the khsatriya nature of the interpreter can be seen. For we know kshatriays to be not much fond of highbrow philosophy, they are concrete people. As soon as Vivekananda added the category of “purusa”, he actually tinted all yoga practices with a simplifying hue.

And the next word – “unmodified” – though added in brackets, comes as a bold philosophical assumption. For if it is unmodified [the Russian version of the translation reads as “natural” – transl.note], we shall finally find ourselves to have it. And the entirety of the spiritual practice is thus set on a different track: we must come close to original, natural form, adopt the “simple life” etc. The idea of breakthrough, evolvement is now lost. It is not the complete range of YS possible interpretations that the reader sees now, but one perspective only.

In the 11th sutra “memory is when the (Vrttis of) perceived subjects do not slip away…” the word asanpramosha is translated as “not slipping away.” But by adding the bracketed (Vrttis of) Vivekananda turns it into “not slipping away of vrittis”. And this is wrong. Patanjali defined memory as not slipping away of anubhava, i.e. of the experience. So why adding here vritti, the vritti that had been clearly determined by Patanjali as pramana, viparyaya, vikalpa, nidra and smritti. How can it not slip away? Moreover, it is incorrect from the position of logic, since memory – smritti – is thus defined as not slipping away of smritti. There’s an obvious logic paradox in this translation.

The 12th sutra. “Their [of Vrttis – transl.note] control is by practice and non-attachment.” The word “control” [in Russian translation the word “mastering” is used – transl.note] once again reveals the kshatriya nature of the author: now we master, control vrittis. Though the original line has the word “nirodha” and reads as follows: abhyāsavairāgyābhyāṃ tannirodhaḥ, i.e. “this nirodha – tannirodhaḥ- is attained by means of abhyasa, the exercise, and vairagya”. Vivekananda translated the nirodha of the line 2 as “restraining”, while here it goes as “control”.

There is another odd addition to the 14th line wandering from one Russian translation to the other one – in case these “translations” are not based on the original. “Its [of abhyasa] ground becomes firm by long, constant efforts with great love (for the end to be attained).” The Sanskrit original, unfortunately, has nothing of great love in it. Or, to, the speak correctly, the root “sev” which basic meaning implies “serve” and “follow” has a figurative meaning of “having sex” in reference to the BDSM-context that was well-known in the Indian erotica, but it is doubtful that it was this meaning that Patanjali implied. Most probably the idea of “great love for the end to be attained” spoke in favour of Vivekananda’s character. He was a passionate person, the “lion of yoga”.

In this way, the translation of Vivekananda, though of flaming spirit, substantially polarizes and simplifies the understanding of yoga, charging the reader with the ideas of the author rather than of Patanjali proper.

The translation of E. P. Ostrovskaya and V. I. Rudoi

In 1992 they published a unique Russian translation of YS done by academic scholars who had “officially” studied yogic texts. The book also included the translation of Vyasa’s commentaries. I read this version immediately after its publishing and I must confess that at that time I did not like it. Why? Because it was rather intricate. And for a long while I was giving it a cold shoulder. And only after some years of studying Sanskrit I’ve found the translation to have many advantages.

The fact is that Yoga Sutras are written in a very specific style, very neat and concise. They go almost without verbs. All actions are expressed either with the help of adverbs, or adjectives, or samasas (compound words) etc., and finding congruent and adequate Russian analogues for these grammar structures is a tough job. While Ostrovskaya and Rudoi did manage! From this perspective this translation variant is simply very nice – it is immaculate from the position of grammar! I should recommend reading this translation to those who study Sanskrit and know the vocabulary but have still not leant the syntaxes – to understand the specifics of the Sanskrit phrasing. But alas – it is absolutely inapplicable for a practitioner, since its language is too specific, it can be understood only by interpreters who did the job and to the followers of their academic tradition. All the others need another translation – into understandable Russian. For instance, the phase “the mind that is deprived of verbal references” shall be an overkill even for a literate one…

To speak in general, there are two schools of academic translation. At one school they believe complete translation is essential, i.e. the translation done in the way that every word of the source text is translated in the target text. The disciples of this approach consider every word to have an equivalent in the other language, and your inability to find it speaks merely about your laziness. And in case in your final translation half of the Sanskrit words has been preserved, then it is just a half-product, it’s like being served a very underdone steak or half-done potatoes with an offer that you finish cooking it yourself.

The other school speaks on the contrary: not every term can be matched with its equivalent. And some terms are to be preserved “as is” or it least furnished with a detailed clarification. I’d rather support the latter idea since having my first degree in physics I understand that not all physical categories can be translated into common language. For instance, how can you explain in ordinary language the meaning of “wave function” or “Hamiltonian [function]”? These are specific terms which essence can be comprehended only by deep delving into math or with the help of other terms.

Ostrovskaya and Rudoi were strictly obeying the first concept: each and every term needs a translation equivalent. And thus it happened that this brilliant, perfect translation has become absolutely unusable. Because the translation was done not just into Russian, but into the Russian of their own. In order to understand this translation a common practitioner needs to understand the logic of the interpretation and the translators’ mode of thought. Besides, many of the translated words have a different meaning in different spheres of the humanitarian (let alone the mundane) knowledge. For instance, the “mind” seen by a philosopher is a far cry from the same when considered from the position of a psychologist.

But he who knows these nuances can still use the translation. Since I know the language and the sutras original reading, I took the trouble to compose a glossary that can be used as a basis for the so called “restored translation”. That is, the text in that all disputable terms with the help of autocorrect function are substituted with their source Sanskrit form.

Here is the glossary:

Klesa – impurity, affect (2)

Vikalpa – mental constructing

Abhyasa – practice

Vairagya – dispassionateness

Isvara – remains untranslated

Purusa – also untranslated

Prasadanam – purification

Samadhi – concentration

Tapas – asceticism

Isvara pranidhana – (reverential) trust in Isvara

Asmita – egoism

Raga – attraction, appeal

Dvesa – hostility

Abhinivesa – self-existent zest for life

Dhyana – yogic contemplation

Karma – unfortunately, left untranslated

Punya – virtue

Apunya – vice

Sanskara – a forming factor

Vasana – unconscious impression

Kaivalya – deliverance and apartness (2)

Yama – self-control

Bhoga – experience

Niyama – adherence to [religious] principles

Pratyaya – cognitive contents

But there is one more problem. The case is that though in lexical terms the translation of many words is correct, the used Russian words have their specific emotional meaningfulness that predesignates the system general perspective. Actually, there are many other nuances as well.

For instance, the word “klesa” was in different parts of the text translated by two different words. In some cases it is rendered as “impurity”, in others it is “affect”. As a result, a person who does not have a Sanskrit dictionary at hand shall not understand that both cases are about one and the same object. Hence confusion in practice appears.

Some words are not clear. For instance, “vikalpa” – “mental constructing”. But who knows what this “mental constructing” actually means. I’m sure the interpreters were perfectly aware of the meaning they were attributing to this word combination. But we are not them…

“Abhyasa” has been translated as “the practice”, though basically it could have been “exercise”, a more traditional variant.

“Vairagya” is “dispassionateness”. Theoretically it is correct, but the word “passion” has both Christian and emotional valence in it. While for a man of our day passions are just very strong emotions. But the original definition given by Patanjali tells us the term “vairagya” implies a different concept. Patanjali defines it as “disengagement, non-attachment of sense organs to the objects,” While in case we consider “passion” in the Christian paradigm, the meaning shall be different. The translation encourages every person to fantasize in their personal way on the ground of their initial cultural paradigm. And this is not reasonable.

The word “prasadanam” in the phrase “chitta prasadanam” is translated as “purification”. And it distorts one’s concept of the practice because it was not purification and cleaning that Patanjali actually meant. The details can be found here but I shall once again emphasize that “prasadanam” is not “purifying” but “collecting the self”. It may have no difference when looking at the text from the point of philosophy. But when we try to use it as a groundwork for the practice, collecting oneself and purifying appear to be totally different ideas to be based on.

“Samadhi” has been translated by the authors as “concentration”. Maybe in this case they were affected by Ballantyne’s interpretation – he also has “concentration” there – or maybe it happened because of some other reasons. But samadhi is not concentration. Samadhi is the state that was triply defined in Yoga Sutras. And from these definitions it is clear that samadhi is a cognitive experience. As for “concentration”, it has its own Sanskrit analogues, like, for instance, “ekagrata” that Yoga Sutras also mention.

The translation of the word “tapas” as “asceticism” it totally ineligible. When we speak about asceticism, they are firm Christian associations that immediately occur. But yoga is not Christianity, it is not a religion in general. Tapas stems from the root-word “tap” that has been preserved in the word “tepid”. In fact, tapas is a means of cumulating inner energy, power.

“Asmita” has been translated as “egoism”. But the definition given in the second section proves it to differ from what a European thinks egoism to be.

“Raga” is rendered as “affinity” [attraction], though we remember the root “rañj” to mean “dye, color”, so in this case “raga” rather means “colouring”. For more details about the difference see here and here.

And then comes “dhyana” – the “yogic contemplation”. This line might have stolen hours of those practitioners who have decided that dhyana is contemplation. Another absurd translation variant – “dhyana is a prayer” – can sometimes also be found. And yoga teachers “inspired” by this interpretation say “close your eyes, imagine some object – this is dhyana”. Yet this is not dhyana but vritti-nidra. That is, sitting and day-dreaming – and not practicing. While dhyana is a specific cognitive process that was also defined in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

The word “karma” has been left untranslated. I think it was not a good idea. A modern European idea of the Hindu “concept” of karma was elaborated by Elena Blavatskaya. She was the first to have written that “karma is the law of cause-and-effect relationship”, “karma is the law of the Universe”, etc. While in Sanskrit “karma” is a nominative case of “karman” – “action”. In the framework of European tradition “karma” has been subjected to ontologization and substantiation as an individual “stuff”, maybe due to the reason that the word “karma” is traditionally left without translation. Whatever the reason, in the text of Yoga Sutras the word “karma” always means “action”, and it could have been translated. “Karmaphala” are the “fruits of the action”, not the fruits of some transcendental karma. “Karmasaya” means “residues from the actions”.

“Punya” – a very important term that means something a person acquires by doing a “right” action. In the framework of Buddhist translation tradition “punya” is sometimes rendered as “spiritual credit”. There are texts that describe the possibility of punya passing from one person to another. I.e. punya is rather a kind of substantiated energy. While here it’s been translated as “virtue”. Yet the word “virtue” with its moralizing connotation somewhat “tenses” the text and brings a Christian undertone into it. “Apunya” is respectively translated as “vice”. Though the following line makes clear that vice it is not.

“Samskara” is a “forming factor” that is not very clear unless a detailed explanation is given. In case we wanted to say it in common language, the most faithful translation [into Russian] would be the word “habit”, while the most adequate psychological term is “dynamic stereotype”.

“Vasana” – “unconscious impression”. In fact, the meaning of vasana is very near to that of samskara. It is just that the word “samskara” stems from the root “kr” by adding the prefix “sam” so that it turns into “co-action”, i.e. “compressed action”. While vasana is a derivative of “vas” – to smell, i.e., the aroma. It’s like “…now everything is ok, but an unpleasant aftertaste remains.” So this “unpleasant aftertaste” is actually vasana, i.e. emotional reminiscence of some event.

The term “kaivalya” has been translated with the help of two different terms – “redemption” and “apartness”. That is already embarrassing. Besides, the word “redemption” also bears a Christian overtone. Though original “kaivalya” has nothing of this sense. “Kevalam” means “to be alone”, individually, and “kaivalya” in an abstract noun that derives from this “kevalam” – the “detachment”, but without the negative connotation that is inevitable in the Russian version.

While the word “bhoga” – “pleasure, delight” – has been ignored by the translators probably for some Christian reasons: they translated it as “experience” as if for the purpose of avoiding the sweet word “pleasure”. In fact, there is a specific Sanskrit word to denote the word “experience” – anubhava. While bhoga is the pleasure proper. The root “bhuj” has two meanings – “to eat” and “to enjoy” (depending on the voice). In this case “to eat” does not seem to be appropriate, so it is still the “pleasure” that the text goes about. Though Vyasa’s interpretation of the word “bhoga” already bears the signs of early Tantra presence.

“Niyama” is “adherence”, as our translators have written, “to religious principles”. But why “religious”? Why bringing a religious component into yoga when yoga is not a religion? Niyama derives from the root “yam” – “to control” – by adding there the prefix “ni” that in this case just intensifies the meaning. That is, “yama” is “control”, while “niyama” is an “even more rigorous control.”

If we bring back all these words and do what I call the “restored translation”, the emerging text in general shall be rather usable.

But first and foremost, the disapprobation of Ostrovskaya and Rudoi translation can be justified by their having translated yoga chitta vritti nirodha as “yoga is cessation of the mind activity”. Of course the translators are very wise and intelligent people, they are scholars, and they never implied the meaning that occurs to common people who read this line. Moreover, there is a dedicated commentary on this line that reads ca.as follows: “the term “vritti” means actual states of the empirical mind which contents is formed by specific pratyayas.” Probably the authors do understand the things they write. But I guess they are the only ones who do. But for, maybe, oriental scholars of the same academic tradition. Yet most people understand this sutra literally as “yoga is cessation of the mind activity”. And there it goes. They say: “But why, yoga IS the cessation of the mind activity”, or “If I’m just sitting there and thinking about nothing – this is yoga” (true and actual quoting of some “practitioners”). Some followers thus decide that the practice of yoga implies “temporal inhibition of the thinking process”. Others suggest “killing dead” with the help of hatha workout in order to attain a state when neither thoughts nor ideas occur. And these are just small potatoes. Because everyone who wanted to be slow on the draw has finally got the permission for this. Yet careful study of the original text shows that Patanjali did not mean intellectual braindeadness to be the objective of Yoga. It is on the contrary – and it is what the whole text is about. The state of yoga is a very active state of mind. But unfortunately the translation telling about cessation of mind activity has stolen the show.

(TO BE CONTINUED)