A series of articles by instructors of the Ukrainian Federation of Yoga, created at the request of The European Union Of Yoga: about personal experience of using yoga methods and knowledge during the war.

Introduction

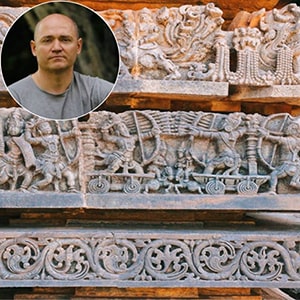

War and yoga. Just a decade ago, these words would have seemed incompatible, especially to the Western yoga community. Yet, the history of yoga tells us a different story. The Bhagavad Gîtâ, perhaps one of yoga’s most revered scriptures, unfolds on a battlefield, where Lord Krishna imparts the wisdom of many yogic paths to a conflicted Arjuna. Similarly, in various tantric traditions, rituals were historically employed in times of conflict, and yogic orders often played active roles in warfare.

Despite these examples, some modern practitioners prefer to idealise yoga, claiming it stands above such brutal realities. But can yoga truly remain apart from the challenges humanity endures? Absolutely not. Yoga is not an abstraction; it exists through its practitioners, who live, struggle, enjoy and persevere in the world as it is. Whether on the fields of Kurukshetra or in the chaos of Trafalgar Square, yoga remains a timeless tool for facing physical, emotional, and spiritual trials.

This article explores what it means to practise yoga amid the ravages of modern war, sharing experiences, raw emotions, and profound questions that demand our contemplation.

The First Days of War: A Time Gap of Swallowed Breath

My apartment in Kyiv. It was still dark outside, the early morning silence shattered by explosions that made the building tremble. I jumped awake, heart pounding, and instinctively knew: ‘These are bomb blasts.’ I recognised the sound from Mariupol in 2014. Within minutes, I grabbed my money, documents and car keys, moving swiftly, without hesitation. My single goal was to collect my daughter and leave the city. Ten minutes. That’s all it took.

Out in the street, it was very quiet, the air was heavy. The few people around moved quickly, but silently. My first conscious exhale came only after ensuring my daughter was safe.

I had witnessed war before, but not like this. This time was different. In 2014, it was a gradual incursion — Russian forces slipping into the Donetsk region in civilian clothes, carrying small arms. But now, a full-scale invasion had begun: tanks, planes, and heavy artillery crashing through our borders, laying waste to cities and mercilessly targeting civilians. The surreal contrast felt impossible to comprehend. Daily life continued in towns, yet at the same time, destruction raged.

At first, my mind resisted the reality, clinging to a sense of disbelief. Images of previous wars – Iraq, Yugoslavia, Chechnya – came to mind, but none of them matched this. The horror felt unique, evoking pictures of the Second World War. Only this time, Russia was the aggressor. The realisation was a painful metamorphosis. The image of Russians as ‘friends’ shattered, replaced by a new, unmistakable identity: we are not them.

Living Within: Discovery of Unknown Emotions

In those first days, I found myself in a dreamlike state. The world had twisted into something grotesque, a part of it actively trying to annihilate me and everything I loved. Reality eventually set in, and the scale of evidence forced acceptance. This was no cruel joke; it was the new, horrifying truth.

Our country of over 40 million sprang into action. People built barricades, volunteered tirelessly, and donated whatever they could. Yoga studios transformed into shelters, distribution centres, and even makeshift workshops for camouflage and supplies. The European Union of Yoga (EUY) played a crucial role, setting up a Facebook group to connect displaced Ukrainian women and children with European families, new homes and support. Yoga teachers across the continent in Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, Switzerland, France, Spain …were helping.

Despite our efforts, our hearts and minds were bound to the front lines, divided between the soldiers and our loved ones trapped in the chaos. Information was scarce, communication difficult. Messenger apps like Telegram kept us connected with real news.

I stayed in constant contact with people who were still in Mariupol, my hometown, which was being hit hard by heavy Russian artillery. My mother, relatives, friends, and many of my yoga students and teachers were still there. Just a week before the war started, I had been in Mariupol myself. I’d met people, we had talked, spent time together, and practised yoga. A few days later, the situation became critical. We discussed evacuation plans, considered whether our yoga studio could serve as a shelter, and shared practical advice on what to do if enemy forces entered the city. Unfortunately, communication with Mariupol soon became difficult, and the news grew grimmer.

My co-teacher, Timur Shevchuk, who also serves as a military officer, called me from the trenches. He had been on the front lines since the very first day, defending against Russian attacks. Our conversations had been brief and serious, but this one was different. He sounded strained, and it was clear that things were getting much worse. The city was being surrounded, and he said this might be our last call. They were pulling back into the city, and communication would likely be cut off.

Eventually, we lost all contact with Timur. Occasionally, when friends or students managed to get messages through, I’d get updates. I found out that another yoga teacher had to leave her home and move into our yoga studio with her family. The space, which had once only seen yoga practice, was now crammed with over 200 people, including children and even pets. There wasn’t much food or water, and the stores were empty. Elena, Timur’s wife and one of my students, told me that supplies were running low and the bombing was relentless. Despite the dire circumstances, some of my students still managed to remain hopeful, though the danger was clear to everyone.

I also had a short call from my mother. She had managed to leave Mariupol and was staying in a small village nearby. They had a bit of food and access to a bomb shelter, where they spent most of their time. That was our last conversation, and I heard nothing more for a month and a half.

This was only a glimpse of what was happening. Mariupol suffered the worst, but other cities were also under attack or living in a state of constant uncertainty. Bad news came from every direction. The emotional toll was immense: anger, disgust, sorrow, fear, disappointment, regret, pride, care. These feelings were powerful and raw, far from the kind of emotions you get from watching a TV series. They were real, deeply unsettling, and they made you feel intensely alive in a way that wouldn’t ever fade.

Yogic Ethics in the Face of War

In studying yoga, we immerse ourselves in principles that shape our perspective on life: ahiṃsā (non-violence), dharma (righteous duty), maitrī (friendliness), karuna (compassion), asteya (non-stealing), and others. We read scriptures, analyse their meaning, debate them with fellow practitioners, and even structure classes around understanding emotions, perception, and thought processes. Often, we come to believe we have internalised these teachings and live according to their values.

War puts these beliefs to the ultimate test. Ideas that once seemed straightforward suddenly get messy and complicated. Faced with the kind of violence and loss that shakes you to your core, even the strongest values start to feel uncertain. You might think of yourself as kind, disciplined, and compassionate, but war has a way of stripping everything down to the bare truth: do those qualities hold up when things get tough, or do they crumble? That forces you to take a hard look at what – and who – really matters. You see your relationships in a new light, uncovering cracks or strengths you didn’t fully realise were there. The clarity can be liberating for some, suffocating for others. Witnessing how war reshapes the lives of those around you is a lesson in itself.

War isn’t only a test of individual growth; it brings relentless moral and cultural challenges. Compatriots are killed daily, whether on the battlefield or by missile strikes that shatter the safety of ordinary places – homes, hospitals, infrastructure. Innocent lives, including children’s, are lost. Properties, businesses, and dreams vanish in an instant. The anguish and anger that arise from this destruction are profound and justified. If someone loses a family member, how can they not feel hatred toward the aggressor? How can ahiṃsā possibly apply here? These are questions Ukrainian yogis struggle with.

Another distressing layer is the rupture of communication with Russian yogis, friends, and family. Some connections remain intact, but others are fractured beyond repair. How do you continue speaking with relatives who express joy over the destruction of your city or believe propaganda that calls for your country’s surrender? The disconnect feels surreal. How does one make sense of loved ones who seem transformed into an echo of propaganda? Is there any hope of staying connected, or has that bond been irrevocably lost? Ukrainian yoga teachers encounter these dilemmas regularly.

Then there’s the issue of asteya (non-stealing). How do we cope when homes, businesses, or entire cities are being destroyed? The struggle to reconcile this principle with the profound sense of loss is deeply real.

Guilt also emerges in unexpected ways. We usually think of guilt as a response to wrongdoing, but here, it manifests differently. People who survive bombings often feel they didn’t do enough to prevent the destruction or save others. This isn’t something that meditation alone can resolve. It’s a visceral, pervasive feeling, demanding an approach rooted in both philosophical understanding and practical support.

These questions aren’t merely theoretical. They are urgent, tangible issues faced by real people. Some of these questions remain unanswered, but the search for understanding continues. Yoga must grapple with the complexity of modern war, exploring its spiritual, karmic, and energetic dimensions. Answers may be slow to come, but the process of seeking them is crucial.

Conclusion

The Bhagavad Gîtâ begins with Arjuna’s despair. Surrounded by friends and family on both sides of the battlefield, he questions war. Krishna’s teachings reshape his understanding, redefining yoga and human purpose.

In this war, I hope the suffering, resilience, and lessons learned will leave a meaningful imprint. Perhaps, like Arjuna, humanity will emerge with a deeper understanding, steering the course of yoga in a new, more compassionate direction.

by Dmytro Danylov, EUY President ad interim, instructor in the Ukrainian Federation of Yoga, head of Yogis Without Borders team